Ignoring water stress as a temporary inconvenience is costing jobs, diverting capital, and jeopardizing the country’s economic targets

For most of us in India’s buzzing cities, the water crisis is an abstract issue—a story of dry farmlands and village distress. It feels distant, belonging to the world of agriculture and monsoons. But a silent, powerful shift is underway. Water scarcity isn’t just a village problem anymore; it’s rapidly becoming a major boardroom constraint, a factory-floor nightmare, and an undeniable threat to India’s GDP growth story. The taps that are running low aren’t just in parched homes; they’re in the industrial clusters that power the nation’s economic engine.

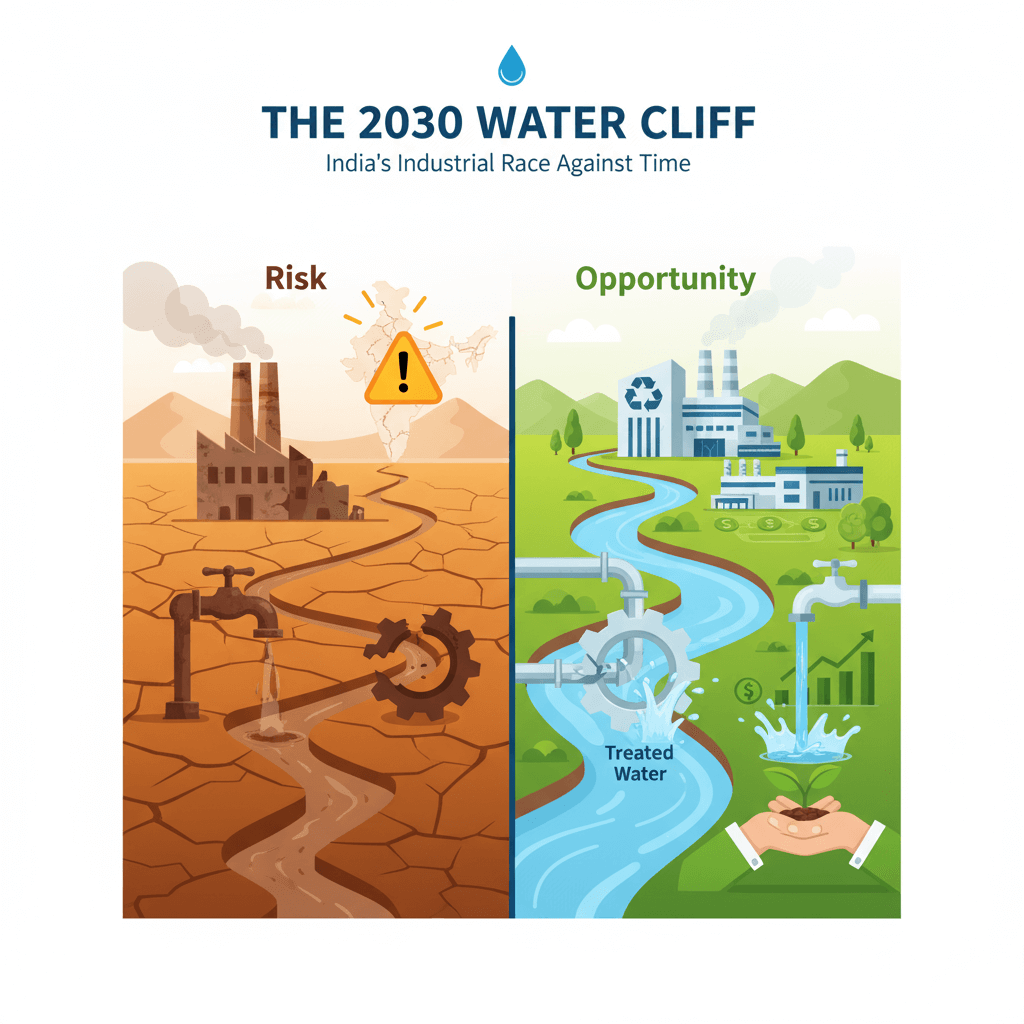

The warnings have been clear for years. NITI Aayog’s Composite Water Management Index brought the crisis into sharp focus, estimating that almost 600 million Indians already face high to extreme water stress. The most unsettling forecast? That the demand for potable water could overwhelm supply by as early as 2030 if we maintain a “business as usual” approach. This isn’t an abstract statistic. Its economic meaning is painfully concrete: when water is scarce, production lines slow down, machinery sits idle because there’s not enough water for cooling or processing, and workers return home early, resulting in lost wages and productivity.

The economic shock from a single plant going offline is far-reaching: industrial belts face unstable power supply, production schedules are disturbed, leading to missed deadlines, and small manufacturers get hit with penalties for delayed delivery.

The demand for water from the industrial sector is growing at a pace few policy debates adequately grasp. Early projections for India’s water future anticipated a rise in industrial water use from about 30 billion cubic metres in 2000 to between 101 and 151 billion cubic metres by 2025 and 2050, respectively. As India aggressively pursues its goal of becoming a global manufacturing powerhouse, building new hubs for textiles, chemicals, automotive components, and electronics, every new factory puts immense pressure on local aquifers, rivers, and reservoirs. This strain is most obvious in industrial estates on the urban fringe—areas once chosen for their “abundant land” and “easy groundwater.” These belts are now entering a critical risk zone. industrial development corporations struggle to maintain assured supply, and smaller units often have to desperately outbid each other for a few essential kilolitres of water to keep boilers running and dyeing machines or cooling towers operational.

The economic damage rarely makes a splash in big headlines. Instead, it accumulates quietly, appearing as a series of seemingly minor, disconnected losses: a day’s production cut here, a cancelled export order there, overtime wages paid to compensate for hours lost when water pressure dropped. For an individual MSME (Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprise), the loss might seem modest. But for an entire industrial cluster, accumulated over a year, these losses can easily run into hundreds of crores of rupees. There’s an even more insidious cost: misdirected capital. An entrepreneur who builds a plant assuming 20 years of stable water supply is often forced to spend fresh capital within a decade on emergency fixes: new storage tanks, water recycling systems, or even partial relocation. These are survival expenses, not investments that create new productive capacity. This diversion of capital is a silent drag on growth for a country focused on job creation and infrastructure development.

Global analyses, including warnings from the World Bank, suggest that continued water scarcity could shave off several percentage points from GDP growth in regions like South Asia by 2050. In the Indian context, the combined effect on agriculture, energy, industry, and health could result in annual economic losses equivalent to multiple percentage points of GDP. Industrial clusters concentrate this risk. A single factory’s water problem is localized; an entire dyeing and processing belt facing cuts is a systemic crisis. This impacts everything from migrant worker incomes to local transporters and ancillary services. Furthermore, reputational risks emerge as global sourcing brands start scrutinizing the long-term water security and environmental compliance of their Indian suppliers.

Climate change is making planning nearly impossible. Irregular, delayed monsoons and long dry spells reduce aquifer recharge, tightening the water budget. Yet, paradoxically, sudden, extreme cloudbursts and urban flooding also cause massive economic damage, destroying infrastructure and causing production losses due to water ingress and power failures. Too much water at the wrong time is proving to be as economically damaging as too little.

The story doesn’t have to be purely one of decline. A growing number of Indian industrial clusters are starting to view water not as a cheap input to be extracted, but as a strategic, shared resource to be managed collectively. We are seeing a rise in Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETPs), adoption of Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) technologies, recycling of process water, and joint investments in local recharge structures. Policy is slowly catching up, moving the conversation beyond emergency tanker solutions. Efforts are underway to improve groundwater data, promote efficient cooling technologies, and incentivize the use of treated sewage water for industrial purposes.

The real danger now is treating water scarcity as a temporary inconvenience. For India’s industrial corridors to remain engines of opportunity rather than islands of vulnerability, water security must be integrated into every major economic decision: plant location, technology, tariffs, and governance. The economic impact of India’s water crisis will not just be measured in lost production; it will be visible in the missed opportunities—the investments that quietly went elsewhere, and the jobs that were never created because water risk was deemed too high. To secure its future growth, India must elevate water from a policy footnote to a central pillar of its economic competitiveness.